Chris Kane, this year’s Terence Freitas Memorial Scholarship winner reflects on his experiences among Indigenous peoples in the Amazon

Since 2009, Associate Professor Flora Lu has been bringing UCSC undergraduates to the Ecuadorian Amazon with her to conduct their own field research with residents of communities with whom she has built longstanding collaborations. The majority of these students have written award-winning senior theses upon their return. The most recent of these researchers-in-training is Christopher Kane, an ENVS senior. He shares some reflections about his experience.

I entered UCSC as a transfer student aiming to pack all of the opportunities the university has to offer into a short two-year stay. I was in awe at Dr. Lu’s work with Indigenous peoples detailing the social, political, and environmental effects of extractive industries on communities of the Ecuadorian Amazon and on the lives of its residents. I thought my ears deceived me when she suggested that I could accompany her to assist with research for the summer of 2014; it was certainly an opportunity wildly out of my comfort zone.

Through secondary research, I became more familiar with the political economy of Latin America, the extractive sector in Ecuador, the paradoxical promises of a populist state, and the interconnectedness of people and their natural environment. Meanwhile, in preparation for this newfound adventure I was exposed to skills that I had not anticipated. Through extensive research and meticulous grant writing – as well as the academic and moral support of Dr. Lu – I was fortunate enough to be offered the National Science Foundation’s Research Experience for Undergraduates award of $4000, as well as $500 from the Porter College Undergraduate Fellowship to pursue my first field expedition.

Time in the field is a world all its own. No matter how much preparation is undertaken – reading up on anthropological theory and ethnographic methodology, the geography, climate, and cultural history of the destination, and even how to a detect and see through the symptoms of culture shock – escaping feelings of vulnerability and discomfort is impossible. I was fortunate enough to have Dr. Lu as my liaison with the community, introducing me to community members, and to a family to stay who put a roof over my head (for which I was quite thankful during regular tropical downpours).

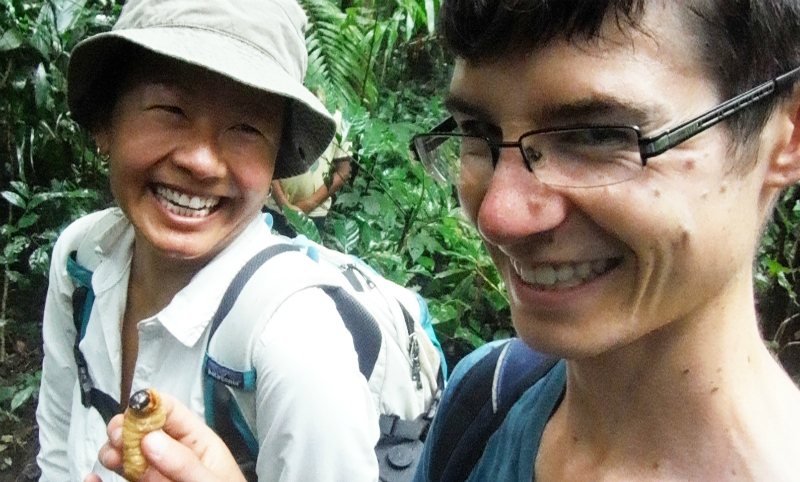

There are experiences from the field that I will never forget: soccer games and exploring with youth in the community, marveling at the tropical flora and fauna of a biodiverse hot-spot, sharing meals with community members and hearing their life stories – all amazing and awe-inspiring. Likewise, there are experiences that I recall as more challenging, deflating, lonely, and humbling: a grueling 9 hour hike between Waorani villages through a mud-ridden rainforest; times of isolation when I literally felt lost in translation; observable environmental pollution brought about by oil roads and company vehicles, and the alcoholism, domestic violence and conflicts that plague the community every Friday evening when men return home from the itinerant weekly market.

My field experience has led to realizations and insights beyond those conveyed in books and anthropological journals. We – referring to academics and students alike in “developed” societies – often view indigenous groups most directly affected by extractive industries as victims, robbed of their traditional culture by the ever-invasive global market. Demonstrating that the continual displacement and undermining of such groups reflects longstanding systems of power is beyond the scope of this newsletter blurb. What is important to recognize, both for understanding dynamic societal groups and the tensions between environmental conservation and socio-economic development, is that these groups are not floundering in response to social, political, economic, and environmental change, but proactively adapting to continue their culture and livelihood in ways which they see fit.

This indeed calls into question whether or not the evolution of traditional native cultures is a “bad” thing. Would you not trade your traditional blowgun and spear for a more technically “advanced” shotgun that offers farther range and increased efficiency for hunting game? Or would you keep your traditional tools, for which you do not have to rely on monetary capital – and thus, external employment – to secure ammunition? With social, environmental, and cultural pros and cons to each, these are both valid decisions, ones that we as anthropologists, ethnographers, academics, and conservationists are not in the position to evaluate as right or wrong.

Through the analysis of a longitudinal dataset provided by Dr. Lu, my thesis examines the diversity of responses to increasing market integration in Indigenous Amazonian communities. The recently awarded Terence Freitas Scholarship will enable me to fund an Ecuadorian anthropologist. She will present my results to the families of the study community and solicit their feedback, which will provide invaluable insight into my interpretations of the findings, insights that will be included in my senior thesis. Do these Waorani residents agree with my findings in regards to their involvement in the market, such as changes in time allocated for commercial versus domestic activities, work versus leisure, and subsistence versus market based consumption? Why do residents think these changes are happening, and what are their methods or reaction and adaptation? Through these first-hand reflections of community residents living these changing realities, we can better understand the effects of market integration on cultural and environmental resilience.