Ecuador's Yasuní-ITT Initiative and the search for new alternatives to oil extraction in Amazonian forests: ENVS faculty member and UCSC students take a closer look

Yasuní National Park, designated in 1989 as a UNESCO Biosphere Reserve, encompasses 3,800-square-miles of rain forest in eastern Ecuador. The biodiversity found there is almost incomprehensible: nearly 600 species of birds, 10 confirmed species of monkeys, and approximately 100,000 insect species in a single hectare, more than in all of the U.S. and Canada combined. It is a "quadruple richness center" with peak species records for amphibians, birds, mammals, and tree communities, and is considered the most biodiverse area in the world. Yasuní corresponds to part of the traditional homelands of the Waorani, a group of hunter-gatherer-horticulturalists who were peacefully contacted for the first time in 1958. Some small sub-groups of Waorani resist contact with the outside world to this day. The name "Waorani" in Ecuador is synonymous with ferocity, they are known for their unpredictable spearing raids and fierce protection of their territory against intruders. Arguably, the fact that Yasuní is still largely intact ecologically is in no small part thanks to the Waorani.

In the early 1990s, Ecuador opened up Yasuní to oil extraction through the creation of a concession known as Block 16. Currently, the Spanish company Repsol is leasing this block, and its predecessor, Maxus, carved a road through the national park, which Repsol has been thus far able to control and prevent large-scale colonization. The only residents in Yasuní are some Kichwa households and Waorani communities. The northeastern part of the national park, called the Ishpingo-Tambococha-Tiputini (ITT) block, has not yet been opened to oil development yet is estimated to contain 820-920 million barrels of heavy crude. In 2007, at the beginning of his presidency, Ecuador's President Rafael Correa presented the Yasuní-ITT Initiative, which outlined his government’s intention to preserve this section of rainforest--to "keep the oil in the ground"--in return for the international community paying his government $350 million per year for ten years ($3.5 billion), then estimated to be about half of the potential earnings from the ITT-block’s oil. Not burning the crude in the ITT block would prevent the release of 410 million metric tons of carbon dioxide, and leaving the forest of the ITT block intact would prevent a further 800 million metric tons of carbon emissions. The Yasuní-ITT Initiative was the first effort in the world to favor conservation over petroleum extraction, and defined Ecuador’s contemporary environmental movement.

In August 2013, ENVS faculty Flora Lu, accompanied by her former UCSC advisees Néstor Silva, Leah Henderson, and Yukari Shichishima, traveled to Yasuní National Park as part of Lu's National Science Foundation funded research project investigating the daily, lived experiences of local families living in zones of oil extraction. One of the Waorani villages along the Repsol oil road exemplifies the complexities and contradictions of Ecuador's quest to achieve conservation and development. The oil company provides menial labor opportunities to these indigenous people, cutting grass with machetes along the pipeline; the Waorani spend only a few hours working, seemingly aware that one oil employee with a weed whacker could do the task more efficiently. Waorani subsistence hunting is discouraged, replaced by fish farming projects and oil company meals in styrofoam boxes. A few months earlier, violence erupted between contacted and uncontacted Waorani--apparently the uncontacted group feel increasingly boxed in and threatened by all the oil activities, and lashed out against those they felt are inadequately protecting the land.

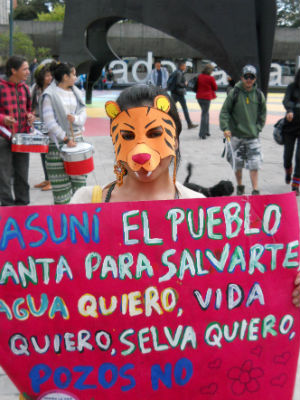

On August 15, as the research team was headed in a motorized canoe towards the Tiputini Biodiversity Station, word came that President Correa had rescinded the Yasuní-ITT Initiative, ostensibly due to lack of funds from the international community. Correa appeared on national television insisting that oil extraction in this last remaining intact area of the national park would be undertaken with great care and responsibility, and that the money was needed to provide social services for the Ecuadorian people. Even before the announcement, Correa's government had already accepted Chinese bids for the ITT block, and the national oil company had already moved full-scale operations into block 31, well within the Yasuní National Park and adjacent to the Tiputini fields that are central to the Yasuní initiative. Street protests in the capital city of Quito erupted at the announcement, with many citizens calling for a popular referendum to decide the fate of ITT. As Flora, Néstor, Leah and Yukari marveled at Saki, Howler, Spider and Woolly monkeys, coral snakes, and jaguar and tapir tracks at the remote Tiputini Biostation, the announcement axing the ITT Initiative cast a dark shadow over the future.

This case study speaks to the intersection of politics, economy, culture and environment. Ecuador, like other countries in South America, has recently seen a rise in power of a government elected explicitly on an anti-neoliberal, anti-imperialist, and pro-resource nationalist platform that seeks to reduce dependency on and dominance of multinational corporations to benefit Ecuadorian people. Critics assert that this administration's "turn to the Left" in actuality burdens local communities and reproduces core-periphery dynamics. The research project seeks to better understand how state agendas and corporate policies transform the landscapes and lives of people like the Waorani.